States of Germany

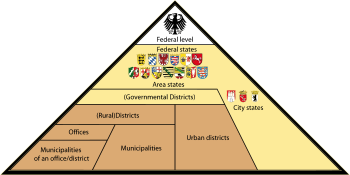

Germany is made up of sixteen Länder (singular Land, German for "land" or "country"), generally referred to in English as states. In official English translations,[1] the term "land" is commonly used. A Land (colloquially but rarely in a legal context also called Bundesland, for "federated state") is one of the partly sovereign constituent states of the Federal Republic of Germany.

The cities of Berlin and Hamburg are states in their own right, while the State of Bremen consists of two cities, Bremen and Bremerhaven. These three are called Stadtstaaten (city-states). The remaining 13 states are called Flächenländer (literally: area states).

States

After World War II, new states were constituted in all four zones of occupation. In 1949, the states in the three western zones formed the Federal Republic of Germany. This is in contrast to the post-war development in Austria, where the Bund (federation) was constituted first, and then the individual states were created as units of a federal state.

The use of the term Länder dates back to the Weimar constitution of 1919. Before this time, the constituent states of the German Empire were called Staaten. Today, it is very common to use the term Bundesland. However, this term is not used officially, neither by the constitution of 1919 nor by the Basic Law of 1949. Three Länder are called Freistaat (free state, republic), i.e., Bavaria (since 1919), Saxony (since 1990), and Thuringia (since 1994). There is little continuity between the current states and their predecessors of the Weimar Republic with the exception of the three free states, and the two city-states of Hamburg and Bremen.

Overview

| Coat of arms | State | Joined the FRG |

Head of government | Gov't coalition |

Bundes- rat votes |

Area (km²) | Population (thous.) |

Pop. per km² |

Capital | German abbrev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png) |

Baden-Württemberg | 1949[2] | Stefan Mappus (CDU) | CDU, FDP | 6 | 35,752 | 10,739 | 300 | Stuttgart | BW |

|

Bavaria (Bayern) |

1949 | Horst Seehofer (CSU) | CSU, FDP | 6 | 70,552 | 12,488 | 177 | Munich (München) |

BY |

|

Berlin | 1990[3] | Klaus Wowereit (SPD) | SPD, The Left | 4 | 892 | 3,395 | 3,807 | – | BE |

|

Brandenburg | 1990 | Matthias Platzeck (SPD) | SPD, The Left | 4 | 29,479 | 2,559 | 87 | Potsdam | BB |

.svg.png) |

Bremen | 1949 | Jens Böhrnsen (SPD) | SPD, The Greens | 3 | 404 | 663 | 1,641 | – | HB |

|

Hamburg | 1949 | Ole von Beust (CDU) | CDU, The Greens | 3 | 755 | 1,774 | 2,309 | – | HH |

|

Hesse (Hessen) |

1949 | Roland Koch (CDU) | CDU, FDP | 5 | 21,115 | 6,075 | 289 | Wiesbaden | HE |

.svg.png) |

Mecklenburg-Vorpommern | 1990 | Erwin Sellering (SPD) | SPD, CDU | 3 | 23,180 | 1,707 | 74 | Schwerin | MV |

|

Lower Saxony (Niedersachsen) |

1949 | David McAllister (CDU) | CDU, FDP | 6 | 47,624 | 7,997 | 168 | Hannover | NI |

|

North Rhine- Westphalia (Nordrhein-Westfalen) |

1949 | Jürgen Rüttgers (CDU) | CDU, FDP | 6 | 34,085 | 18,029 | 530 | Düsseldorf | NW |

|

Rhineland-Palatinate (Rheinland-Pfalz) |

1949 | Kurt Beck (SPD) | SPD | 4 | 19,853 | 4,053 | 204 | Mainz | RP |

|

Saarland | 1957 | Peter Müller (CDU) | CDU, FDP, The Greens | 3 | 2,569 | 1,050 | 409 | Saarbrücken | SL |

|

Saxony (Sachsen) |

1990 | Stanislaw Tillich (CDU) | CDU, FDP | 4 | 18,416 | 4,250 | 232 | Dresden | SN |

|

Saxony-Anhalt (Sachsen-Anhalt) |

1990 | Wolfgang Böhmer (CDU) | CDU, SPD | 4 | 20,446 | 2,470 | 121 | Magdeburg | ST |

|

Schleswig-Holstein | 1949 | Peter Harry Carstensen (CDU) | CDU, FDP | 4 | 15,799 | 2,833 | 179 | Kiel | SH |

|

Thuringia (Thüringen) |

1990 | Christine Lieberknecht (CDU) | CDU, SPD | 4 | 16,172 | 2,335 | 144 | Erfurt | TH |

History

Federalism has a long tradition in German history. The Holy Roman Empire comprised numerous petty states. The number of territories was grossly reduced during the Napoleonic Wars. After the Congress of Vienna 39 states formed the German Confederation. It was dissolved after the Austro-Prussian War and replaced by the North German Federation under Prussian hegemony. The war left Prussia dominant in Germany, and German nationalism would compel the remaining independent states to ally with Prussia in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, and then to accede to the crowning of King Wilhelm as German Emperor. The new German Empire included 25 states, three of them Hanseatic cities and the imperial territory of Alsace-Lorraine. The empire was dominated by Prussia, which controlled 65% of the territory and 62% of the population. After the territorial losses of the Treaty of Versailles, the remaining states continued as republics. These states were gradually de facto abolished under the Nazi regime via the Gleichschaltung process, as the states were largely superimposed by the Nazi Gau system.

During the Allied occupation of Germany after World War II, borders were redrawn by the allied military governments. No single state comprised of more than 30% of either population or territory. This was done with the intent of preventing any one state from being as dominating as Prussia had been in the past. Initially, only some of the pre-War states remained, i.e., Baden (partly), Bavaria, Bremen, Hamburg, Saxony, and Thuringia. The “hyphenated” Länder such as Rhineland-Palatinate, North Rhine-Westphalia and Saxony-Anhalt owed their existence to the occupation powers and were created of Prussian provinces and smaller states.

Upon founding in 1949, West Germany had eleven states. These were reduced to nine in 1952 when three south-western states (South Baden, Württemberg-Hohenzollern and Württemberg-Baden) merged to form Baden-Württemberg. Since 1957, when the French-occupied Saarland was returned ("little reunification"), the Federal Republic consisted of ten states, which are called the Old States today. West Berlin was under the sovereignty of the Western Allies and neither a Western German state nor part of one. However, it was in many ways integrated with West Germany under a special status.

East Germany (GDR) originally consisted of five states (i.e., Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Thuringia). In 1952, the Länder were abolished and the GDR was divided into 14 administrative districts instead. Soviet-controlled East Berlin, despite officially having the same status as West Berlin, was declared the GDR's capital and its 15th district.

Just prior to the German reunification on 3 October 1990, East German Länder were simply reconstituted in roughly their earlier configuration as five new states. The former district of East Berlin joined West Berlin to form the new state of Berlin. Henceforth, the 10 "old states" plus 5 "new states" plus the new state Berlin add up to 16 states of Germany.

Later, the constitution was amended to state that the citizens of the 16 states had successfully achieved the unity of Germany in free self-determination and that the Basic Law thus applied to the entire German people. Article 23, which had allowed “any other parts of Germany” to join, was rephrased. It had been used in 1957 to reintegrate the Saarland into the Federal Republic, and this was used as a model for German reunification in 1990. The amended article now defines the participation of the Federal Council and the 16 German states in matters concerning the European Union.

The Länder can conclude treaties with foreign countries in matters within their own sphere of competence and with the consent of the Federal Government (Article 32 of the Basic Law).

The description free state (Freistaat) is merely a historic synonym for republic—a description used by most German states after the abolishment of monarchy. Today, Freistaat is associated emotionally with a more independent status, especially in Bavaria. However, it has no legal meaning. All sixteen states are represented at the federal level in the Bundesrat (Federal Council), where their voting power merely depends on the size of their population.

New delimitation of the federal territory

Article 29 of the Basic Law states that the division of the federal territory into Länder may be revised to ensure that each Land be of a size and capacity to perform its functions effectively. The somewhat complicated provisions regulate that [r]evisions of the existing division into Länder shall be effected by a federal law, which must be confirmed by referendum.

A new delimitation of the federal territory has been discussed since the Federal Republic was founded in 1949 and even before. Committees and expert commissions advocated a reduction of the number of the Länder; scientists (Rutz, Miegel, Ottnad etc.) and politicians (Döring, Apel and others) made sometimes very far-reaching proposals for redrawing boundaries but hardly anything came of these public discussions. Territorial reform is sometimes propagated by the richer Länder as a means to avoid or limit fiscal transfers.

To date the only successful reform was the merger of the states of Baden, Württemberg-Baden and Württemberg-Hohenzollern to the new state of Baden-Württemberg in 1952. The fusion of the two states of Berlin and Brandenburg was rejected in a referendum in May 1996.

Outline

Prelude

Article 29 reflects a debate on territorial reform in Germany that is much older than the Basic Law. The Holy Roman Empire used to be a loose confederation of large and petty principalities under the nominal suzerainty of the emperor. Approximately 300 states existed at the eve of the French Revolution in 1789.

Territorial boundaries were essentially redrawn as a result of military conflicts and interventions from the outside: from the Napoleonic Wars to the Congress of Vienna, the number of territories decreased from about 300 to 39; in 1866 Prussia annexed the sovereign states of Hanover, Nassau, Hesse-Kassel and the Free City of Frankfurt; the last consolidation came about under Allied occupation after 1945.

The debate on a new delimitation of the German territory started in 1919 as part of discussions about the new constitution. Hugo Preuss, the father of the Weimar constitution, drafted a plan to divide the German Reich into 14 roughly equal-sized Länder. His proposal was turned down due to opposition of the states and concerns of the government. Article 18 of the constitution enabled a new delimitation of the German territory but set high hurdles: Three fifth of the votes handed in, and at least the majority of the population are necessary to decide on the alteration of territory. In fact, until 1933 there were only four changes of the German map: The 7 Thuringian states united in 1920, whereby Coburg opted for Bavaria, Pyrmont joined Prussia in 1922, and Waldeck did so in 1929. Any later plans to break up the dominating Prussia into smaller states failed because political circumstances were not favorable to state reforms.

After the National Socialists seized power in January 1933 the Länder increasingly lost importance. They became administrative regions of a centralised country. Two changes are to be noted: On 1 January 1934 Mecklenburg-Schwerin united with the neighbouring Mecklenburg-Strelitz and by the Greater Hamburg Act (Groß-Hamburg-Gesetz) from 1 April 1937 the area of the city state was extended, while Lübeck lost its independence and became part of the Prussian province of Schleswig-Holstein.

Before the foundation of the Federal Republic of Germany

Between 1946 and 1947, new Länder were established in all four zones of occupation: Bremen, Hesse, Württemberg-Baden, and Bavaria in the American zone; Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein, Lower Saxony, and North Rhine-Westphalia in the British zone; Rhineland-Palatinate, Baden, Württemberg-Hohenzollern and the Saarland—which later received a special status—in the French zone; Mecklenburg(-Vorpommern), Brandenburg, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Thuringia in the Soviet zone.

In 1948, the military governors of the three Western Allies handed over the so-called Frankfurt Documents to the minister-presidents in the Western occupation zones. Among other things they recommended to revise the boundaries of the West German Länder in a way that none should be too big or too small in comparison to the others.

As the premiers did not come to an agreement on this question, the Parliamentary Council was supposed to address this issue. Its provisions are reflected in Article 29. There was a binding provision for a new delimitation of the federal territory: the Federal Territory must be revised ... (paragraph 1). Moreover, in territories or parts of territories whose affiliation with a Land had changed after 8 May 1945 without referendum, people were allowed to petition for a revision of the current status within a year after the promulgation of the Basic Law (paragraph 2). If at least one tenth of those entitled to vote in Bundestag elections were in favour of a revision, the federal government had to include the proposal into its legislation. Then a referendum was required in each territory or part of territory whose affiliation was to be changed (paragraph 3). The proposal should not take effect if within any of the affected territories a majority rejected the change. In this case, the bill had to be introduced again and after passing had to be confirmed by referendum in the Federal Republic as a whole (paragraph 4). The reorganization should be completed within three years after the Basic Law had come into force (paragraph 6).

In their letter to Konrad Adenauer the three western military governors approved the Basic Law but suspended Article 29 until a peace treaty was agreed upon. Only the special arrangement for the southwest under Article 118 could enter into force.

The foundation of Baden-Württemberg under Article 118 of the Basic Law

In southwestern Germany territorial revision seemed to be a top priority since the border between the French and American occupation zones was set along the Autobahn Karlsruhe-Stuttgart-Ulm (today the A8). Article 118 allowed that [t]he division of the territory comprising Baden, Württemberg-Baden and Württemberg-Hohenzollern into Länder may be revised, without regard to the provisions of Article 29, by agreement between the Länder concerned'. Since no agreement was reached, a referendum was held on 9 December 1951 in four different voting districts, three of which approved the merger (South Baden refused, but was overruled as the result of total votes was decisive). On 25 April 1952 the three former Länder merged into Baden-Württemberg.

The petitions of 1956

With the Paris Agreements West Germany regained (limited) sovereignty. This triggered the start of the one year period as set in paragraph 2 of Article 29. As a consequence, eight petitions for a referendum were launched, six of which were successful:

- Reconstitution of the Land Oldenburg 12.9%

- Reconstitution of the Land Schaumburg-Lippe 15.3%

- Reintegration of Koblenz and Trier into North Rhine-Westphalia 14.2%

- Reintegration of Rheinhessen into Hesse 25.3%

- Reintegration of Montabaur into Hesse 20.2%

- Reconstitution of the Land Baden 15.1%

The latter petition had originally been rejected by the Federal Minister of the Interior in reference to the referendum of 1951. However, the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany ruled that the plebiscite was unlawful because it had disadvantaged Baden's population. The two Palatine petitions (for a reintegration into Bavaria and integration into Baden-Württemberg) failed with 7.6% and 9.3%. Further requests for petitions (Lübeck, Geesthacht, Lindau, Achberg, 62 Hessian communities) had already been rejected as inadmissible by the Federal Minister of the Interior or were withdrawn as in the case of Lindau. The rejection was confirmed by the Federal Constitutional Court in the case of Lübeck.

The development up to the 1961 Constitutional Court decision

If a petition was successful paragraph 6 of Article 29 stated that a referendum should be held within three years. Since the deadline passed on 5 May 1958 without anything happening the Hesse state government filed a constitutional complaint with the Federal Constitutional Court in October 1958. The complaint was dismissed in July 1961 on the grounds that Article 29 had made the new delimitation of the federal territory an exclusive federal matter. At the same time, the Court reaffirmed the requirement for a territorial revision as a binding order to the relevant constitutional bodies.

The constitutional amendment of 1969

The grand coalition decided to settle the 1956 petitions by setting binding deadlines for the required referendums. The referendums in Lower Saxony and Rhineland-Palatinate were due till 31 March 1975, the one in Baden was due till 30 June 1970. The quorum for a successful vote was set to one-quarter of those entitled to vote in Bundestag elections. Paragraph 4 stated that the vote should be disregarded if it contradicted the objectives of paragraph 1.

The Ernst Commission

In his investiture address, given on 28 October 1969 in Bonn, Chancellor Willy Brandt, proposed that the government would consider Article 29 of the Basic Law as a binding order. For this purpose an expert commission was established, named after its chairman, the former Secretary of State Professor Werner Ernst. After two years of work the experts delivered their report in 1973. It provided an alternative proposal for both northern Germany and central and southwestern Germany. In the north, either a single new state consisting of Schleswig-Holstein, Hamburg, Bremen and Lower Saxony should be created (solution A) or two new states, one in the northeast consisting of Schleswig-Holstein, Hamburg and the northern part of Lower Saxony (from Cuxhaven to Lüchow-Dannenberg) and one in the northwest consisting of Bremen and the rest of Lower Saxony (solution B). In the Center and South West either Rhineland-Palatinate (with the exception of the Germersheim district but including the Rhine-Neckar region) should be merged with Hesse and the Saarland (solution C), the district of Germersheim would then become part of Baden-Württemberg. Or the Palatinate (including the region of Worms) would be merged with the Saarland and Baden-Württemberg, the rest of Rhineland-Palatinate would then merge with Hesse (solution D). Both alternatives could be combined (AC, BC, AD, BD).

At the same time the commission developed criteria for classifying the terms of Article 29 paragraph 1. The capacity to perform functions effectively was considered most important, whereas regional, historical, and cultural ties were considered as hardly verifiable. To fulfill administrative duties adequately, a population of at least five million per Land was considered as necessary.

After a relatively brief discussion, and mostly negative responses from the affected Länder, the proposals were shelved. Public interest was limited or non existent.

The referendums of 1970 and 1975

The referendum in Baden was held on 7 June 1970: With 81.9% the vast majority of voters decided for Baden to remain part of Baden-Württemberg, only 18.1% were opting for a reconstitution of the old Land Baden.

The referendums in Lower Saxony and Rhineland-Palatinate, were held on 19 January 1975:

- Reconstitution of the Land Oldenburg 31%

- Reconstitution of the Land Schaumburg-Lippe 39.5%

- Reintegration of Koblenz and Trier into North Rhine-Westphalia 13%

- Reintegration of Rheinhessen into Hesse 7.1%

- Reintegration of Montabaur into Hesse 14.3%

Hence, the two referendums in Lower Saxony were successful. As a consequence legislature was forced to act and decided that both Oldenburg and Schaumburg-Lippe remain with Lower Saxony. Justification was that a reconstitution of Oldenburg and Schaumburg-Lippe would contradict the objectives of paragraph 1. An appeal against the decision was rejected as inadmissible by the Federal Constitutional Court.

The constitutional amendment of 1976

On 24 August 1976 the binding provision for a new delimitation of the federal terrritory was altered into a mere discretionary one. Paragraph 1 was rephrased, now putting the capacity to perform functions in the first place. The option for a referendum in the Federal Republic as a whole (paragraph 4) was abolished. Hence a territorial revision was no longer possible against the will of the affected population.

The reintroduction of the Länder in East Germany

The debate about a territorial revision started again shortly before the German reunification. While scientists (Rutz and others) and politicians (Gobrecht) suggested introducing only two, three or four Länder in the GDR, legislation reintroduced the five Länder that existed until 1952, however, with slightly changed boundaries.

The constitutional amendment of 1994

Article 118a was introduced into the Basic Law and provided the possibility for Berlin and Brandenburg to merge without regard to the provisions of Article 29, by agreement between the two Länder with the participation of their inhabitants who are entitled to vote.

Article 29 was again modified and provided an option for the Länder to revise the division of their existing territory or parts of their territory by agreement without regard to the provisions of paragraphs (2) through (7).

The rejected merger of Berlin and Brandenburg in 1996

The state treaty between Berlin and Brandenburg was approved in both parliaments with the necessary two-thirds majority, but in the popular referendum of 5 May 1996 about 63 % voted against the fusion.

Conclusion

A new delimitation of the federal territory keeps being debated in Germany though "there are significant differences among the American states and regional governments in other federations without serious calls for territorial changes"[4]. However, "the argument the proponents of boundary reform in Germany make is that the German system of dual federalism requires strong Länder that have the administrative and fiscal capacity to implement legislation and pay for it from own source revenues. [...] But in spite of these and other arguments for boundary reforms, action has not been taken ...[5].

Structure of government

| Germany |

This article is part of the series: |

|

|

|

Constitution

Legislature

Judiciary

Executive

Divisions

Elections

Foreign policy

|

|

Other countries · Atlas |

The Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany, the federal constitution, stipulates that the structure of each Federal State's government must "conform to the principles of republican, democratic, and social government, based on the rule of law" (Article 28[1]).

Most of the states are governed by a cabinet led by a Ministerpräsident (Minister-President), together with a unicameral legislative body known as the Landtag (State Diet). The states are parliamentary republics and the relationship between their legislative and executive branches mirrors that of the federal system: the legislatures are popularly elected for four or five years (depending on the state), and the Minister-President is then chosen by a majority vote among the Landtag's members. The Minister-President appoints a cabinet to run the state's agencies and to carry out the executive duties of the state's government.

The governments in Berlin, Bremen and Hamburg are designated by the term Senate. In the three free states of Bavaria, Saxony and Thuringia the government is referred to as the State Government (Staatsregierung), and in the other ten states the term Land Government (Landesregierung) is used.

Before January 1, 2000, Bavaria had a bicameral parliament, with a popularly elected Landtag, and a Senate made up of representatives of the state's major social and economic groups. The Senate was abolished following a referendum in 1998.

The states of Berlin, Bremen, and Hamburg are governed slightly differently from the other states. In each of these cities, the executive branch consists of a Senate of approximately eight selected by the state's parliament; the senators carry out duties equivalent to those of the ministers in the larger states. The equivalent of the Minister-President is the Senatspräsident (President of the Senate) in Bremen, the Erster Bürgermeister (First Mayor) in Hamburg, and the Regierender Bürgermeister (Governing Mayor) in Berlin. The parliament for Berlin is called the Abgeordnetenhaus (House of Representatives), while Bremen and Hamburg both have a Bürgerschaft. The parliaments in the remaining 13 states are referred to as Landtag (State Parliament).

Politics

Politics at the state level often carries implications for federal politics. Opposition victories in elections for State Parliaments, which take place throughout the federal government's four-year term, can weaken the federal government, because state governments have assigned seats in the Bundesrat, which must also approve many laws after passage by the Bundestag (the federal parliament).

State elections are viewed as a barometer of support for the policies of the federal government. If the parties of the governing coalition lose support in successive state elections, those results may foreshadow political difficulties for the federal government. In the early 1990s, the opposition SPD commanded a two-thirds majority in the Bundesrat, making it particularly difficult for the governing CDU/CSU-FDP coalition to achieve the constitutional changes it sought; by 2003 the situation was the reverse, with an SPD-led government being severely hindered by a large CDU majority in the Bundesrat. This led to Konrad Adenauer and Gerhard Schröder losing the federal chancellorship in 1963 and 2005 respectively because their governments became unable to decisively act, thus losing popular support, all because of the efforts of the various state leaders in the Bundesrat in blocking legislation.

The powers of the state governments and legislatures in their own territories have been much diminished in recent decades due to ever-increasing federal legislation. A commission has been formed to examine the possibility of instituting a clearer separation of federal and state powers. The states, in particular, are responsible for cultural development, law enforcement and the educational system in its entirety (both primary and secondary schools, and the universities as well). In Germany, the military is a federal affair. Hence, the states have no armies.

Further subdivisions

The city-states of Berlin and Hamburg are subdivided into boroughs. The state of Bremen consists of two urban districts, Bremen and Bremerhaven, which are not contiguous. In the other states there are the following subdivisions:

Landschaftsverbände

Landschaftsverbände ("area associations"): The most populous state of North Rhine-Westphalia is uniquely divided into two Landschaftsverbände, one for the Rhineland, one for Westphalia-Lippe. This was meant to ease the friction caused by uniting the two culturally quite different regions into a single state after World War II. The Landschaftsverbände retain very little power today.

The constitution of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern in §75 states the right of Mecklenburg and Vorpommern to form Landschaftsverbände, although these two constituting parts of the Land are not represented in the current administrative division.

Regierungsbezirke

Regierungsbezirke (governmental districts): The large states of Baden-Württemberg, Bavaria, Hesse, North Rhine-Westphalia and Saxony are divided into administrative regions, or Regierungsbezirke. In Rhineland-Palatinate, the Regierungsbezirke were dissolved on January 1, 2000, in Saxony-Anhalt on January 1, 2004 and in Lower Saxony on January 1, 2005.

Kreise

Kreise (administrative districts): Every state (except the city-states Berlin, Hamburg and Bremen) consists of rural districts (Landkreise), District-free Towns/Cities (Kreisfreie Städte, in Baden-Württemberg also called urban districts, Stadtkreise), cities that are districts in their own right, or Kommunalverbände besonderer Art (local association of a special kind, see below). The state of Bremen consists of two urban districts, while Berlin and Hamburg are states and urban districts at the same time.

There are 313 Landkreise and 116 Kreisfreie Städte, making 429 districts altogether. Each consists of an elected council and an executive, who is chosen by either the council or the people, depending on the state, and whose duties are comparable to those of a county executive in the United States, supervising local government administration. The Landkreise have primary administrative functions in specific areas, such as highways, hospitals, and public utilities.

Kommunalverband besonderer Art

A Kommunalverband besonderer Art (local association of a special kind) is an amalgamation of one or more Landkreise with one or more Kreisfreie Städte to form a replacement of the aforementioned administrative entities on the level of Kreise. They are entities to implement simplification of administration on that level. Typically a district-free city or town and its urban hinterland are grouped in a Kommunalverband besonderer Art. Such an organization requires the issue of special laws by the governing state, since they aren't covered by the normal administrative structure of the respective states.

In 2010 only three Kommunalverbände besonderer Art exist.

- Region Hannover (district Hannover). Formed in 2001 out of the previous rural district Hannover and the district-free city of Hannover.

- Regionalverband Saarbrücken (district association Saarbrücken). Formed in 2008 out of the predecessor organization Stadtverband Saarbrücken (city association Saarbrücken), which was already formed in 1974.

- Städteregion Aachen (city region Aachen). Formed in 2009 out of the previous rural district Aachen and the district-free city of Aachen.

Ämter

Ämter ("offices" or "bureaus"): In some states there is an administrative unit between districts and municipalities. These units are called Ämter (singular Amt), Amtsgemeinden, Gemeindeverwaltungsverbände, Landgemeinden, Verbandsgemeinden, Verwaltungsgemeinschaften or Kirchspiellandgemeinden.

Gemeinden

Gemeinden ("municipalities"): Every rural district and every Amt is subdivided into municipalities, while every urban district is a municipality in its own right. There are (as of 6 March 2009[update]) 12,141 municipalities, which are the smallest administrative units in Germany. Cities and towns are municipalities as well, which have city rights or town rights (Stadtrechte). Nowadays, this is mostly just the right to be called a city or town. However, in older times it included many privileges, such as the right to impose its own taxes or to allow industry only within city limits.

Gemeinden are ruled by elected councils and an executive, the mayor, who is chosen by either the council or the people, depending on the Bundesland. The "constitution" for the Gemeinden is created by the states and is uniform throughout a Bundesland (except for Bremen, which allows Bremerhaven to have its own constitution).

Gemeinden have two major policy responsibilities. First, they administer programs authorized by the federal or state government. Such programs typically might relate to youth, schools, public health, and social assistance. Second, Article 28(2) of the Basic Law guarantees Gemeinden "the right to regulate on their own responsibility all the affairs of the local community within the limits set by law." Under this broad statement of competence, local governments can justify a wide range of activities. For instance, many municipalities develop and expand the economic infrastructure of their communities through the development of industrial parks.

Local authorities foster cultural activities by supporting local artists, building arts' centres, and by having fairs. Local government also provides public utilities, such as gas and electricity, as well as public transportation. The majority of the funding for municipalities is provided by higher levels of government rather than from taxes raised and collected directly by themselves.

In five of the German states, there are unincorporated areas, in many cases unpopulated forest and mountain areas, but also four Bavarian lakes that are not part of any municipality. As of January 1, 2005, there were 246 such areas, with a total area of 4167.66 km² or 1.2 percent of the total area of Germany. Only four unincorporated areas are populated, with an aggregate population of about 2000. The following table gives an overview.

| State | 01. Jan. 2004 | 01. Jan. 2000 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Area in km² | Number | Area in km² | |

| Bavaria | 216 | 2725.06 | 262 | 2992.78 |

| Lower Saxony | 23 | 949.16 | 25 | 1394.10 |

| Hesse | 4 | 327.05 | 4 | 327.05 |

| Schleswig-Holstein | 2 | 99.41 | 2 | 99.41 |

| Baden-Württemberg | 1 | 66.98 | 2 | 76.99 |

| Total | 246 | 4167.66 | 295 | 4890.33 |

The table shows that in 2000 the number of unincorporated areas was still 295, with a total area of 4890.33 km². Unincorporated areas are continually being incorporated into neighboring municipalities, wholly or partially, most frequently in Bavaria.

See also

- Elections in Germany

- List of cities in Germany

- List of subnational entities

- For a list of German states prior to 1815 see List of states in the Holy Roman Empire

- New federal states

- State Police Landespolizei

- Composition of the German Regional Parliaments

References

- ↑ Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany - Published by: German Bundestag

- ↑ In 1949 the states of Baden, Württemberg-Baden and Württemberg-Hohenzollern joined the federation. These were united in 1952 into Baden-Württemberg.

- ↑ Berlin has only officially been a Bundesland since reunification, even though West Berlin was largely treated as a state of West Germany.

- ↑ Gunlicks, Arthur B.: German Federalism and Recent Reform Efforts, in: German Law Journal Vol. 06 No. 10, p. 1287

- ↑ Gunlicks, Arthur B.: German Federalism and Recent Reform Efforts, in: German Law Journal Vol. 06 No. 10, p. 1288

External links

|

|||||||||||||

|

||||||||